The Armstrong Whitworth AW55 Apollo

The Forgotten Airliner

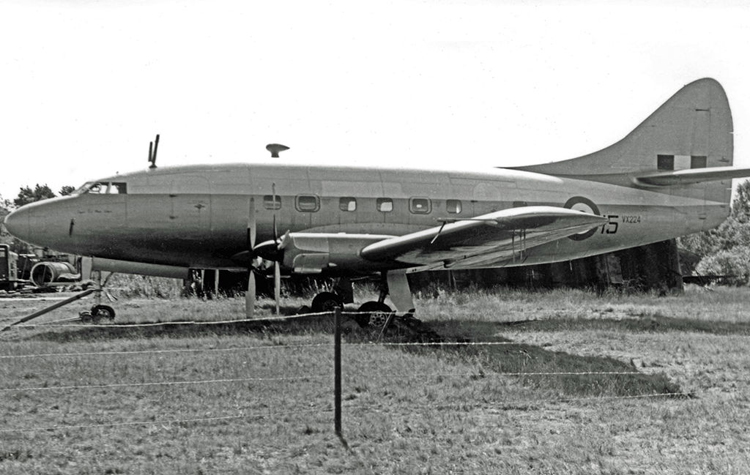

Photograph – RuthAS, CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

More quality photographs are available on the BAE Systems website at this link

This paper is a brief history of the Armstrong Whitworth AW55 Apollo turbo-prop airliner.

The previous papers in this series of monographs describe a number of different aeroplanes manufactured by Sir WG Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Ltd. (AWA), Coventry. Some of these machines were successful both technically and commercially, others were not. The AW 55 Apollo turbo-prop airliner fell decidedly into the second category.

Whilst the second world war was still being fought a government committee was established in1942 to consider and formulate post-war British civil aviation policy. It was called the Brabazon Committee, chaired by Lord Brabazon of Tara. The committee’s remit was to consider the various types of civil aircraft that would be required in the future, and then lay down broad specifications for their development.

One of the Brabazon Committee’s specifications (Type II) was for a medium range airliner with accommodation for up to 24 passengers. Because of committee disagreement this specification was divided into two subsections; viz, IIA for piston engine powered machines and IIB for turbo-prop powered aircraft. The aeroplanes that ultimately emanated from this particular specification were as follows:

IIA – The Airspeed Ambassador with two Bristol Centaurus Mk.661 Sleeve Valve Piston Engines;

IIB – The Vickers VC2 Viscount with four Rolls-Royce Dart Turbo-prop Engines with centrifugal flow compressors; and –

The Armstrong Whitworth AW55 Apollo with four Armstrong Siddeley AS1/AS2 Mamba Turbo-prop Engines with axial flow compressors.

Thus, the Apollo was derived from the Brabazon Committee requirement IIB, and a contract for two airframes to Air Ministry Specification C16/46 was made through the aegis of the Ministry of Supply (MoS).

Preparatory work on the Apollo began at AWA Baginton, probably in 1946 or early1947, commencing with a wooden mock-up. The machine featured a low cantilever wing married to a circular section pressurised fuselage. Four Armstrong Siddeley AS1/AS2 Mamba axial flow turbo-prop engines, situated in very slim wing mounted nacelles, were selected to power the aircraft. This was the world’s first application of an axial flow turbo-prop engine in a civil airliner (other than purely experimental installations). Due to the extreme slimness of the engine nacelles the main elements of the tricycle type undercarriage had to retract directly into the wings rather than the inboard nacelles. A mid-positioned horizontal stabiliser and elevator completed the empennage.

Work on the first prototype Apollo (VX 220) civil registration G- AIYN, commenced in late 1947 with the machine being completed in March 1949. The maiden flight of the first prototype Apollo took place on 10th April 1949, with Chief Test Pilot Eric Franklin at the controls and WH “Bill” Else in the second seat. Early flights indicated that directional and longitudinal stability were unsatisfactory and modifications to the airframe would be required. These were comparatively easy problems to remedy. However, the major concern with the aircraft was not the airframe but the Mamba turbo-prop engines. They proved to be unreliable and delivered well below their predicted rated output of 1,010 shaft-horsepower. These were difficult problems which rendered the aircraft seriously underpowered. After only 9 hours flying time the temporary Certificate of Airworthiness was revoked pending further engine development.

Unfortunately for the Apollo its main competitor, the Vickers Viscount, was not experiencing the same sort of difficulties; the Rolls Royce Dart being a far superior and infinitely more reliable engine than the Mamba. In fact, the Dart went on to be an extremely fine and long-lived engine, with several thousand constructed and in service with many airlines worldwide. The Mamba in contrast never attained the same status in civil aviation as the Dart, its only major application being in the Fairey Gannet maritime reconnaissance aircraft. Here it was used as the Double Mamba, which could be operated as a combined twin engine unit using a common gearbox, or as individual units, either engine capable of being shut down to promote economy when used in the maritime reconnaissance role.

Eventually a second prototype Apollo (VX 224) G-AMCH joined the flight development programme. The engine problems persisted though, and it was becoming increasingly obvious that the Apollo, saddled with its Mamba engines, was never going to rival the Vickers Viscount; an altogether better airframe /engine combination. Furthermore, the Viscount’s seating capacity had been increased beyond the Brabazon Committee’s original specification, making the aircraft even more economical to operate.

Photographs of the period illustrate the Apollo prototypes fitted with various propeller arrangements. Some images show three and four-bladed propeller combinations on the same machine; the inboard engines having the four-bladed variety. Without expert knowledge one can only speculate on the reasons for these arrangements. Perhaps they were experimental to cure vibration or other problems associated with the engines or attempts to maximise thrust from the under-performing Mambas.

Although an extremely elegant looking aeroplane, the Apollo was never going to be a serious competitor to the Viscount. If AWA from the outset had not been wedded to Armstrong Siddeley engines and had designed the Apollo around the Rolls-Royce Dart, the story may have been rather different. The Viscount went on to be one of the most successful post war British civil aeroplanes, with well over four hundred machines being constructed – the majority for export. The Dart engine was of course also used in many other aeroplanes of both British and foreign manufacture. A Dart engined Apollo could perhaps have enjoyed some of this success. We shall never know.

In June 1952 a decision was made, presumably by AWA management, to cancel all further commercial development of the Apollo. As both Apollo prototypes technically belonged to the government, in September 1952 the first prototype machine was directed to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down. A year later the second prototype followed. This machine subsequently went to the Empire Test Pilots’ School for use in multi-engine pilot training. The first prototype was broken up in 1955 and the second prototype airframe ended its days in the Structures Department at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough. Here it was used until the 1970s for static water tank testing purposes, undoubtedly adding to the fund of knowledge on metal fatigue in pressurised aircraft structures.

The point has been made several times in previous papers in this series that it was the inability of AWA to capture some of the post-war civil aviation market that was to have serious implications for the company a decade or so later. At the time of the Apollo’s failure AWA was awash with military contracts, so the ramifications were not immediately apparent or serious. It was only when AWA’s military work eventually dried up in the 1960s that the full effect upon the company of being just a one trick pony became a critical factor and hastened its demise.

References:

- Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, The Archive Photograph Series, Ray Williams, Chalford, 1998

- World Encyclopaedia of Aero Engines, Bill Gunston, Guild Publishing, London, 1986

Copyright © JF Willock December 2021