One Brick: Several Stories

Webster Hemming & Sons 1945-Present Day

Part 4:Webster Hemming & Sons 1945

This article concludes the story of the brickworks, but it remains open to correction and future expansion as more material will inevitably come to light. We would be very happy to hear of such additions to the story.

A note on the Hemmings

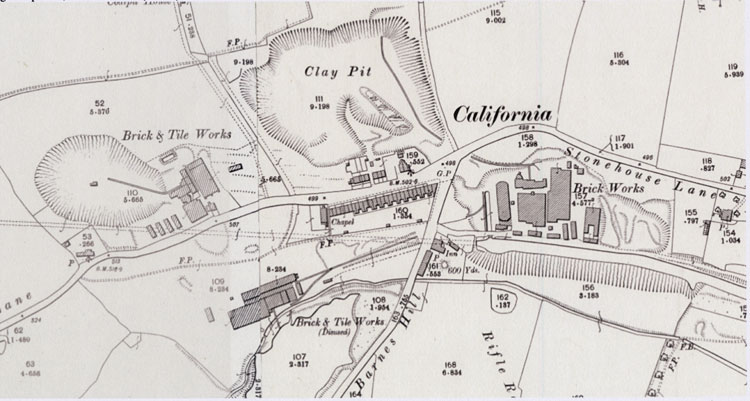

The Hemming family were well known in Midland brickmaking circles and on the death of Roger Hemming in 2008, it was stated that the family’s connection with the trade went back 200 years. This can be traced back to Reuben Hemming (Senior) who was part of the brick-making boom (The Great Brick Rush, perhaps?) that engulfed the settlement known as California, not on the west coast of America but west of the city of Birmingham near Weoley Castle! California possessed many brickworks, and in the 1881 Census Reuben Hemming was listed as residing in California, working as a ‘Brick Burner’. His son, also Reuben, was only 6 at the time. The Hemmings must have been living in the housing in the middle of the map below.

Ten years later in 1891 we find the Hemming family in Francis Road, Hay Mills, Birmingham, with father and son both working as brickyard labourers. Francis Road is close to several brickyards in the vicinity.

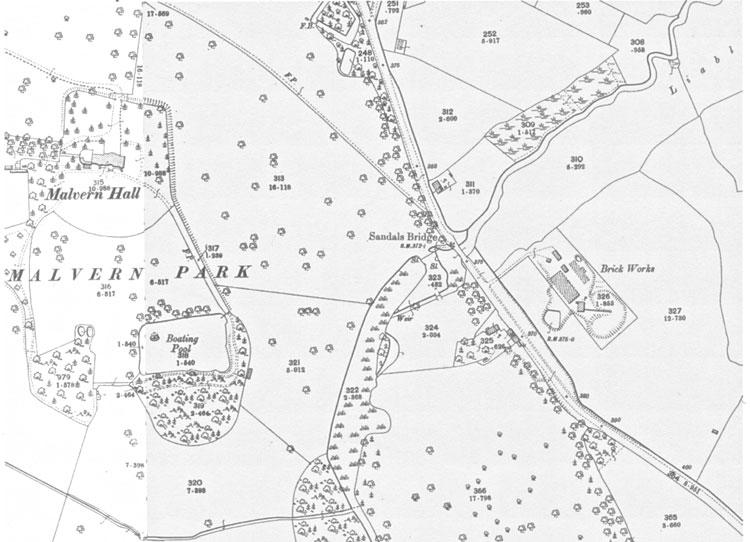

An added complication to this story is the establishment of a brickworks by a certain Henry Hemming around 1895, and this was the Waterloo Brickworks on Speedwell Road (on the right of the map). This was eventually sold to brothers Frank and William Bayliss in 1913, and Henry Hemming moved to a new works at Wood End, Earlswood. It has so far not been possible to disentangle the various Hemmings involved, and what the relationship was between Henry and Reuben – if any.

The story of Birmingham’s Bricks has been extensively researched by Martyn Fretwell. His wonderful blog is a treasure trove of information. uknamedbricks.blogspot.com

A further potential source of confusion is the title of ‘Midland’ employed in the naming of firms. For example, in 1895 the Wilkins and Webster’s operation was at the Midland Brick and Tile Works, Stoney Stanton Road, Coventry whilst at the same time The Midland Brick Company was operating from Garrison Lane, Birmingham. In 1915, Kelly’s Directory lists the Midland Brick Company also operating from Warwick Road, Solihull.

At broadly the same time, Reuben Hemmings (junior) is listed in the 1911 Census as having moved to Blythe Cottage, Warwick Road, Solihull, working as a brickmaking labourer. The assumption is that he was employed at the nearby Solihull Brick Company, a business that he was subsequently to assume responsibility. Future references to Reuben Hemmings list him as residing at 143 Hampton Lane, as well as his two sons Reginald Stanley living at 71 Hampton Lane, and Percy Frederick at 31 Beechnut Lane, all in Solihull.

The obituary of 90-year-old Reuben Hemming in the Coventry Evening Telegraph of 9th. December 1964 recorded “For many years Mr. Hemming was Chairman of the Solihull Brick Company and when that closed down he became Chairman of the new company – Webster’s Hemming & Sons – formed in Coventry in 1938. He had lived at ‘Townsville’, The Beeches, Harbury for the past five years, and prior to that for fifteen years in Poole, Dorset.”

Webster’s, Hemming and Sons 1945-Present Day

So in 1938, Reuben Hemming, together with his two sons, Reginald Stanley and Percy Frederick, took over the Webster’s yard in Coventry, and changed the name to Webster’s, Hemming & Sons. The previous article (part 3) demonstrated that his early ownership of the works had something of a false start, with the site requisitioned by the Admiralty during the Second World War, with the air raid sirens a new landmark in the area.

The choice of ‘Reginald Stanley’ as first names for his son aroused the fanciful notion in me that Reuben Hemming had chosen the name of one of Warwickshire’s most famous brickmakers – Reginald Stanley of Nuneaton – as first names for his son. Almost certainly complete nonsense – pure speculation – but it remains an interesting thought nevertheless!

On the WIAS visit to the brickworks in 1993, our guide, Mr. Hall, described Reginald as “an extremely lively character”, though precisely what he meant by this was never revealed.

His son Roger became the managing director of the firm, married Soad Jones in 1958 at Henley in Arden, and eventually Roger’s son, James, became managing director of the firm.

Roger, third from left, at his marriage to Soad 1958 – Soad on his right. Other persons unidentified – Could the gentleman on the right of the picture even be Reginald S. Hemming?

Like his father, Roger also seems to have been a redoubtable character, and achieved notoriety in Coventry when he fought off masked raiders at his yard in Stoney Stanton Road in 1989. Roger’s obituary in the Coventry Evening Telegraph of 31st. October 2008 recalled the event:

The chairman of a well-known Coventry brickmaking firm has died at the age of 80.

Roger Hemming, whose family had roots in the brickmaking industry going back 200 years, was hailed as a hero in 1989 when he was stabbed while fighting off masked raiders at his yard in Stoney Stanton Road.

Originally from Solihull, Mr Hemming’s great-grandfather, along with his grandfather and uncle, took over the old Websters yard in 1938 when the company name was changed to Websters, Hemming and Sons. After doing his National Service, Roger Hemming joined the family firm and went on to run the business. After retirement he continued to turn up at least once a week for work until the day he died.

Mr Hemming, who lived in Fen End, near Balsall Common, was proud of the fact that most of the homes in Coventry were built with bricks from his yard. He leaves a widow, Soad, and is survived by two of their three sons, James, now the managing director of the business, and David. The couple’s first child, Roger, died in a car accident some years ago.

Back in 1989 Mr. Hemming was stabbed twice in the neck after fighting off burglars who broke into his premises. He threw a fire extinguisher at one of the raiders, checked that an office worker was safe and then noted down the number of a getaway car before realising he was bleeding. He was taken to Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital to have a blood clot removed from his neck.

His son James said: “Brickmaking was in my father’s blood, his family had been making bricks in Birmingham and then Coventry for the past 200 years.”

The current company operates as Midland Brick, and the company publicity states:

‘Midland Brick continues the long tradition of the Hemming family in the brick industry. The family started brick making over 200 years ago by making bricks for the Grand Union Canal around Birmingham. This led to the family owning and running several Brickyards in Birmingham, Solihull and Coventry. Now no longer making bricks but continuing in the industry by having bricks made for them using knowledge gained over such a long period’.

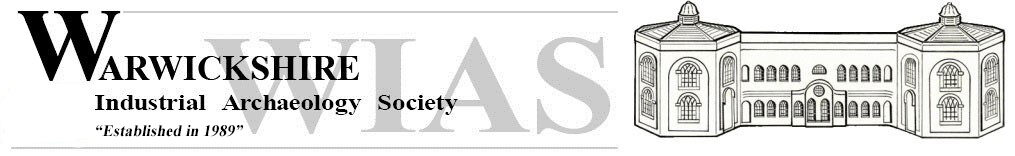

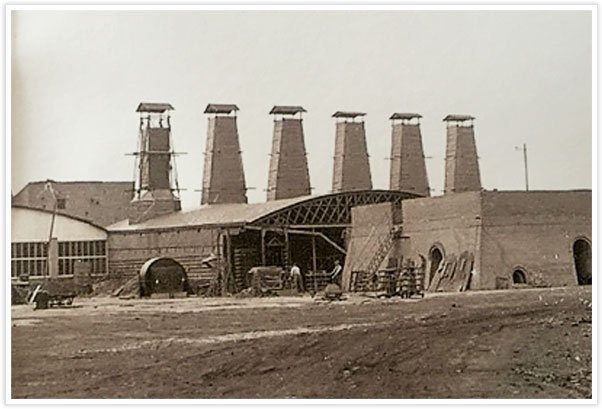

- Two historic photographs from the Midland Brick website, including the wartime air raid sirens

- Two historic photographs from the Midland Brick website, including the wartime air raid sirens

The story of Hemming’s brick in the post-war period follows that of many brickmakers in the country. The surge of post-war demand for housing placed pressures on capacity, but at the same time the use of other materials for construction locally and beyond made for an unpredictable demand. Many small brickworks could not compete against the larger concerns such as the London Brick Company, although Webster’s, Hemming & Sons managed to survive until late in the day, finally closing in the 1990s, with the remaining buildings being demolished prior to the conversion to a recreational area.

Advertisements appeared in the local press immediately after the war seeking ‘Skilled Brickyard Workers and Labourers’ with ‘the highest rate of pay’ offered. (Coventry Evening Telegraph 4th. January 1947). A fifth kiln was added in 1950, and the company ran a series of adverts lasting many years through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s offering

BRICKS!

FACING BRICKS, COMMONS, BRIQUETTES ETC.

LARGE or SMALL QUANTITIES SUPPLIED

PRICES AND SAMPLES ON APPLICATION

WIAS VISIT TO THE BRICKWORKS 1993

Fortunately, a visit was arranged to the works in May 1993, and a report written by John Selby was included in the Society’s magazine RETORT! I reproduce that report here:

“Once the clay is extracted from the pit, the clay is left to ‘weather’ for at least three months, preferably six to twelve months, resulting in a friable texture. It is then loaded onto the mill conveyor belt. A curtain of heavy chains at the belt conveyor loading bin ensures that the tipping by the mechanical shovel is evened out in the feed to the Kibbler roller pan. The Kibbler rollers are drums with knuckles. They break down the large lumps before it is passed on to the pug mill.

The pugging process works and tempers the clay to make it ‘plastic’ and of uniform consistency. Various additives are included at this stage – e.g. barium carbonate to improve brick quality; wood pulp to reduce power necessary to drive the mill; and coal slack to assist in the burning of the bricks.

After the pug mill, the clay passes to the brick-making shed. It was here that our Chairman, Toby Cave, pointed out the interesting Belfast roof trusses supporting the structure. In this shed, modern machinery produces extruded bricks, with ingenious wire-cutting machines producing bricks of the required size. The machine also produces the rusticated effect via a dragging action across the face of the brick.

After being loaded automatically on the pallets, the ‘green’ bricks are then transferred on an old rail car system driven by 220DC to a bank of drying ovens (heated by paraffin fuel). Each chamber takes between 5,000 and 6,000 green bricks and the drying takes place over 3 to 4 days at 180°F.

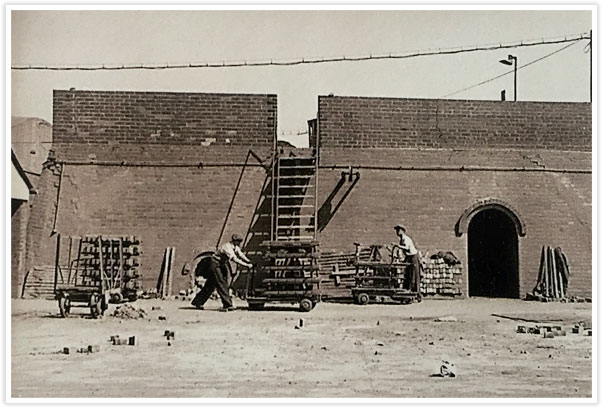

The final process involves the firing of the bricks in the Hoffman kiln. This was re-built in 1950. The 18-chamber kiln has a two-week cycle of setting, firing, cooling and drawing. With a light oil fuel, a temperature of 1020°F is reached in the firing stage.

- Brick Kilns

- Brick Kilns

We finished the tour by looking into the working pit, noting how the developments in hydraulic excavators had removed the necessity of blasting out the hard lower levels of clay.

- WIAS members explore the site in 1993

- WIAS members explore the site in 1993

- WIAS members explore the site in 1993

There are photographs of the works on the WIAS website but there is also an excellent selection taken by Cliff Jones in 2012. They can be accessed by clicking this link

Webster’s Bricks, Coventry | Cliff Jones Photographs – Flickr

Other evidence of the operation of the works can be gleaned from The Coventry History Forum – a website full of personal reminiscences.

NormK from Bulkington records in 2012:

“In the early days the Hoffman kiln was fired with coal, later they changed over to oil firing and then gas firing. The chimney smoked up until the time of gas burners. The Hoffman got in such a bad state because it was brick built and had to be continually repaired, the brick arches would sag and became dangerous. We rebuilt a lot of it over the years. This kiln is still there but not used.

To replace it we built 3 steel ones which are heavily insulated to prevent the heat burning the steel away and can be fed by forklift truck with lowered masts which makes the job a lot easier because the Hoffman was all handball in and out because of the low arches.

When I retired from there they produced between 20/30,000 bricks a day which ain’t bad considering all the plant used was original and broke down on a regular basis. You would not want to work there because it was serious hard graft.”

THE CREATION OF WEBSTER’S PARK

Concerns about the long-term future of the site on the Stoney Stanton Road began to emerge, and a plan emerged involving the creation of a public park. This would involve compulsory purchase of the site by the council, and in 1979 they sought to accelerate the process by attempting to limit the period of permitted clay extraction to a further five years. Mr. Alfred Wood county planner for the West Midlands County Council decided that such a limit could not be put in place, and that there was sufficient clay for to supply the works for another 50 years.

As John Selby commented in his write-up of the 1993 visit:

“Extraction is still taking place, but the huge hole is currently being back-filled with Coventry’s refuse. This pit also contained a much-disputed SSSI which is also being covered. The demands of refuse disposal, geological conservation and raw-material extraction for the brick-making industry seemed to be delicately balanced”.

As with many extractive industries, the exposure of strata reveals information about the land’s formation, and Webster’s clay-pit was no exception. In fact, the clay-pit contained features that were of considerable significance for those involved in geological conservation.

In fact, there had been two clay-pits, one 40ft. deep which had been in-filled, and another 160ft. deep, with a sump to clear excess water into the adjacent canal. On the WIAS visit in 1993, Mr. Hall recalled a team of geologists from Cambridge exploring the site, making quite a contrast to the usual workforce.

I have no geological expertise, but the topic is well covered in the writings particularly of Colin Prosser, Head of Earth Sciences, English Nature. It was identified as one of the Case Studies in the English Nature publication ‘Geological Conservation: a Guide to Good Practice’, published in 2006. This set out the justification for SSSI status:

‘The site was notified as an SSSI for Carboniferous sandstones and mudstones of the Enville Formation. The exposures at Webster’s Clay-pit represented the only available exposure of alluvial plain deposits within the Enville Formation. The site has also yielded a distinctive fossil flora, reflecting more humid conditions than other sites of the same age and was considered the best British site for studying Upper Palaeozoic conifers.’

The only problem was that the clay-pit was declared an SSSI after planning permission to landfill the site had already been granted. Therefore, ‘under planning law, the planning permission for landfilling the site took precedence over the statutory nature conservation designation and the associated legislation aimed at conserving the SSSI.’

The demise of the clay-pit is also covered by Colin Prosser in an article “Webster’s Clay-pit SSSI: Going, Going, Gone” in Earth Heritage Magazine 19 Winter 2002/2003.

Representations were made by various authorities to get the decision overturned, principally because the local planning authority wanted to see pit filled in as part of the long-term goal to develop much-needed green space in this urbanized part of Coventry. Efforts were made to persuade the council to retain a conservation section, but this was rejected, again on the grounds that an exposed geological face would represent health and safety issues in a public recreational area.

The process of infilling was commenced and Webster’s Hemming & Sons placed adverts in local papers advising that TIPPING FACILITIES FOR APPROXIMATELY 100,000 CU. YDS. were available.

- The pit – before infilling and partially covered

- The pit – before infilling and partially covered

Webster’s Park today 2020

- Webster’s Park

- Webster’s Park

The site of the former brickworks has been transformed, with further developments still in progress. I thought, however, on a recent visit, that an information board might serve the park well, outlining the former activities on the site. As it was, there was a slightly unloved feel about Webster’s Park, with litter and graffiti contributing unwelcome features to this important location for Coventry’s industrial history.