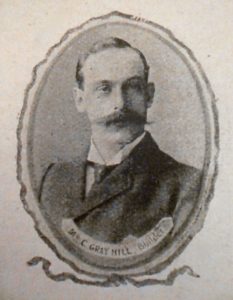

C.GRAY HILL – ONE BRICK; SEVERAL STORIES

One of the joys of what might loosely be termed ‘research’ is the way in which the most mundane of items can produce both interest and surprise. So it was with the desire to find out more about some of Coventry’s lesser-known brickyards. The task of trying to seek out some information about these yards gradually led to some fascinating examples of entrepreneurial initiative. The other great danger of doing all this is that someone else has already covered the ground, and a re-invention of the wheel takes place. My hope is that this is not the case with the following example.

Let us start with a brick retrieved from a demolition site in Coventry, carrying the name C GRAY HILL COVENTRY.

Charles Gray Hill was born in Highbury, London in 1864 and spent his early years in the metropolis, only coming to Coventry in 1881. He was the son of Thomas Hill, partner in the London building firm of of Messrs Higgs and Hill.

Charles Gray Hill was also a building contractor, and in 1886 he took over the business and premises of Coventry Alderman Mr. James Marriott, Much Park Street. As the Coventry Herald of January 22nd 1886 reported –

JAMES MARRIOTT

Desires to inform his Friends and his Public generally that he has Transferred his Business as a Builder and Contractor to MR. CHARLES GRAY HILL, on whose behalf he respectfully solicits a continuation of that confidence and patronage so generously accorded to himself for upwards of forty years.

Directly beneath there is a welcoming response from Charles Gray Hill, assuring the inhabitants of Coventry and neighbourhood that all works entrusted to him would receive his personal attention, and would be executed with ‘economy, stability and dispatch’.

The Coventry Herald of 23 August 1895 carries an advert for the company’s products –

GRAY HILL

MUCH PARK STREET, COVENTRY

Manufacturer of Tiles, Finials, 6in., 8in. and 9in. Quarries.

Wire Cut and Facing Bricks etc.

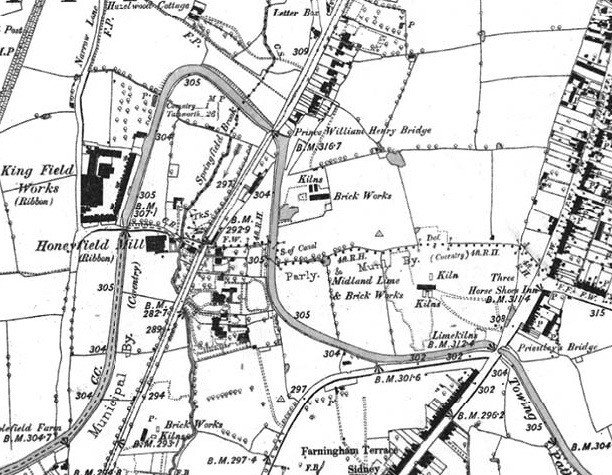

He also had a brickyard in The Foleshill area, with access from the Foleshill Road. It was situated close to the Prince William Henry Bridge, a location confirmed in the Coventry Evening Telegraph of 17th. October 1891.

‘Mr. Hill carries out his brickmaking on land leased from the Hon. Cecil Irby, near the Foleshill Road just above the canal bridge, distinguished by the name of the adjacent public-house, the Prince William Henry. For years clay had been raised and bricks made by hand on the same ground, and nearly five years ago (1886) Mr. Hill took over the place from Mr. James Marriott’.

This is land which is close to the brickworks ‘Midland Brick and Lime Works’, later Wilkins & Websters brickworks, with the limits set by the Foleshill Road to the west, the Stoney Stanton Road to the east and the Coventry Canal to the south.

The reporter then provides a wonderful description of the brickworks under the heading ‘BRICKMAKING BY MACHINERY’, extolling the benefits of mechanisation in the industry via the example of Mr. Charles Gray Hill.

‘The development of modern enterprise machinery has been adapted to the making of bricks with a view to economy, certainty, and rapidity of production, as well as improvement in quality and appearance. The horse mill has been superseded by powerful steam machinery for the purpose of tempering the raw clay; the hand-maker, with his tub of water, strike, brick-mould, and stock-board, has been replaced by the pug-mill, and the smoky, extravagant kiln put out by the erection of a large structure with a tall shaft, and constructed on scientific principles. It is only when brickmaking is on a considerable scale that moulding by machinery can exhibit its greatest advantages, and these advantages are clearly demonstrated at the yard of Mr. Charles Gray Hill, the widely-known Coventry builder.

There was not a machine on the ground until four years ago, and comparison with the present advanced state of the plant speaks for itself of the energy, determination and capital put into the concern by the owner.

There then follows a detailed description of the brick-making process at this time, which is worth repeating in full:

First of all, there are the clay-pits, the source of the raw material. There only used to be one, and the greatest depth it was worked was about eight feet, when a layer of red sandstone stopped further proceedings. Mr. Hill has got through this, and goes down 30 feet, only to meet with a very thick bed of rock, which he means to either cut through, or else tunnel the clay on either side of the pit. In earnest of his purpose there is a steam rock drill ready for commencing blasting operations. From both pits clay is being got out and thrown into trolley tubs, which when full are drawn up an incline laid with rails to the grinding mills – a mill to each pit.

The No. 1 pit is the larger, and has the more powerful mill to feed. As soon as a full tub reaches the summit its contents are tipped and fed into a hungry-looking opening on the way to a most ferocious-looking pair of kibblers, or revolving drums with numerous teeth, that masticate the mass, and pass it further on down the double pair of rollers below. These effect further reduction, and a clay leaves them in what might be called a half-digested condition. It is then fed into the hopper of the pug-mill, an interesting and useful piece of machinery, which is commonly known as the sausage machine. Its principal feature is a horizontal cylinder, containing a central shaft fitted with strong pug blades placed in a spiral manner, and which thoroughly mix and prepare the plastic clay, at the same time pushing it forward to a pressing roller which forces the moving mass through a wooden die, or mould, at the mouth of the mill. If plain bricks are wanted then the mould is a plain one, and the “sausage” produced is of the same unpretentious character; if some variation of pattern is required then the mould partakes of a more elaborate character accordingly. When the mill has forced out a sufficient length of prepared clay of the exact shape of the pattern set in the mould, all that remains to be done is to cut into single bricks by wires arranged in a rocking frame. Thus at one forward movement of the frame nine bricks are cut, and these are at once run off to low sheds for the next process in the work – drying.

In the drying process, instead of the old system of stacking in ‘hacks’ in the open air, and covering with straw in the cold season, the ‘green’ bricks are laid out in sheds, heated by the exhaust steam from the engine. This gives a great economy of time. But the new patent kiln is perhaps the most useful auxiliary in the manufacture. This is a series of arched chambers, connected by passages to one main flue, each passage having dampers to regulate the heat at any given point. In one part of the kiln the bricks are being set ready for burning. They then get the chance to become further dried, it might be said partially baked, by the hot air passing from the heated chambers, where another set are being burned, then in their turn they go through the burning process, and are finally left ready for drawing.

This means that in the kiln, which is one of Jung’s, an improvement upon the Hoffman system, there is a continual round of setting, drying, burning, and drawing going on. Above the chambers there is a second floor used as a workshop for making the best pressed bricks by machinery, and here the heat is further utilised for the drying of this important class of goods.

It is remarkable what a demand there has sprung up for ornamental terracotta work, and specimens are at hand of what Mr. Hill can produce, and there is no doubt that he will be able to report further progress in a short time. At present he is busy on bricks in all sorts of patterns, and his average turn-out is somewhere between 120,000 and 15000 a week. This is probably only an indication of what is to come’.

Well an indication of what was to come was that Hill eventually sold his works to nearby Websters brickworks, a move precipitated by the proposed building of the Websters Mineral Railway in 1899. Websters Annual Report to shareholders of 1899, in a justification for the proposed railway to link with the LNWR (Leamington to Nuneaton) line, the report stated –

“With this object in mind, the directors report that they have recently acquired the brickworks of C. Gray Hill. These works adjoin those of our Company, and have a frontage onto the proposed line of the railway.” (Coventry Evening Telegraph 22 August 1899)

(See article on ‘Wilkins, Webster, Hemming’)

Charles Gray Hill: building contractor

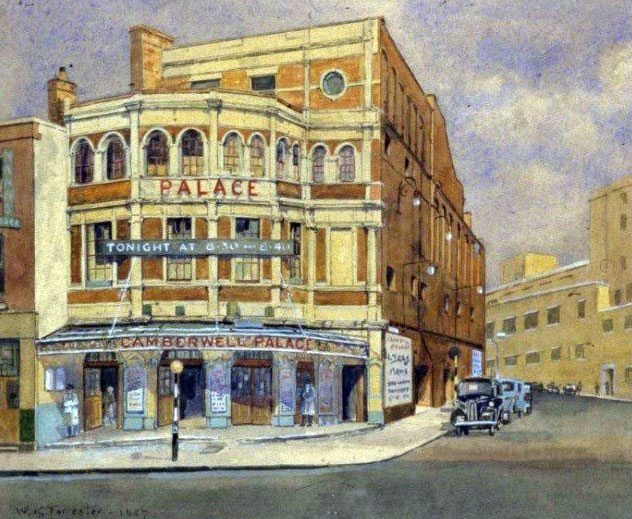

At a relatively young age, Hill seemed to have developed a growing reputation as a building contractor, developing some important connections, including the world of London theatres. In a productive partnership with architect Ernest Woodrow A.R.I.B.A, he had been appointed the contractor to build a number of theatres in London.

One of these was the Camberwell Palace of Varieties, and the laying of the Memorial Stone and the Opening Ceremony were reported in The Music Hall and Theatre Review (an unlikely source of information on Coventry builders!).

The Review for 7th. July 1899 included details of the Laying of the Memorial Stone, with the reporter obviously much taken by the role played by renowned entertainer of the period Miss Vesta Tilley, describing her as looking “extremely well”.

‘AT 3.25, or thereabouts, by the clock last Monday afternoon, Miss Vesta Tilley, after performing certain graceful evolutions with a handsome silver-plated trowel, specially designed for the purpose, declared the memorial stone of the new Camberwell Palace of Varieties to be “well and truly laid”. The announcement was received with loud cheers by the company who had accepted the invitation of the directors to be present at the ceremony, echoed back by the workforce stationed aloft the on the walls of the new building.’

The Music Hall and Theatre Review of December 15th. 1899 reported that ‘The structure has been erected by a contractor who had had large experience in theatre buildings, for Mr. C.Gray Hill, of Coventry, has erected The Granville Theatre of Varieties, Walham Green, The Shakespeare Theatre, Clapham Junction, and many other theatres’.

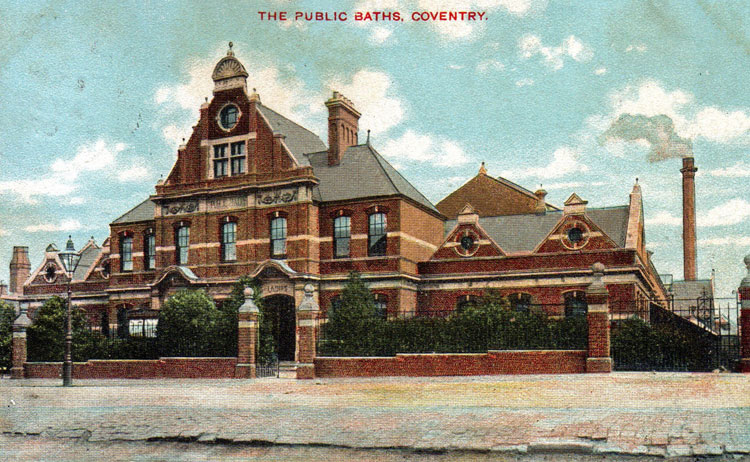

Coventry also received the benefits of his abilities, with the Public Baths, Priory Street built in 1894. Details of this can be found www.historiccoventry.co.uk

Interestingly, Hill used bricks from a Kenilworth brickyard for the façade of the building. The report on the laying of the foundation stone included ‘The façade will stand out in bright Cherry Orchard bricks, relieved with alternate bands of white Portland stone, the gable rising high and clear of the one-storey wings, which will be broken up with pediment gablets and capped with Portland stone pediments.’

Other projects included the Opera House in Hales Street (1899) and the Foleshill branch police station, fire station, and free library, opened in 1903. His home ‘Broadwater’ in Kenilworth Road was among a number of large residences constructed by his firm in the locality.

In 1900 he moved from his brick activities in Much Park Street to ‘more commodious premises in Godiva Street’. George Loveitt advertised the sale of the Much Park Street site – ‘Offices, Joiners’ Shop, and capital Workshop, formerly part of Messrs. Calcott Bros., Cycle Works, Much Park Street’. As it turned out, this was not the last occasion that Hill would work in this street.

A change of direction

On 14th. May 1896 he had married Louise Maude Singer, daughter of George Singer, cycle and later motor magnate. In fact Hill had done some extremely important work for Singer, including the building of the Canterbury Street Factory and Coundon Court, Singer’s home.

The Midland Daily Telegraph allocated a large number of column inches to the wedding, and gave it the title of ‘INTERESTING WEDDING IN COVENTRY’. It was held in the Warwick Road Congregational Church, a singularly appropriate location in view of the fact that Charles Gray Hill had erected it.

It was clearly an important occasion in the Coventry social calendar and was a ticketed event in view of the anticipated crush of guests, well-wishers and interested onlookers. The report described in meticulous detail the floral decoration of the church, the dresses worn by the members of the wedding party, and the list of presents –‘very numerous, and of costly character’. An address with 226 signatures from the managers, foremen, office staff and workers of Messrs. Singer & Co was also presented to Miss Singer, together with an ornate table lamp and candelabra.

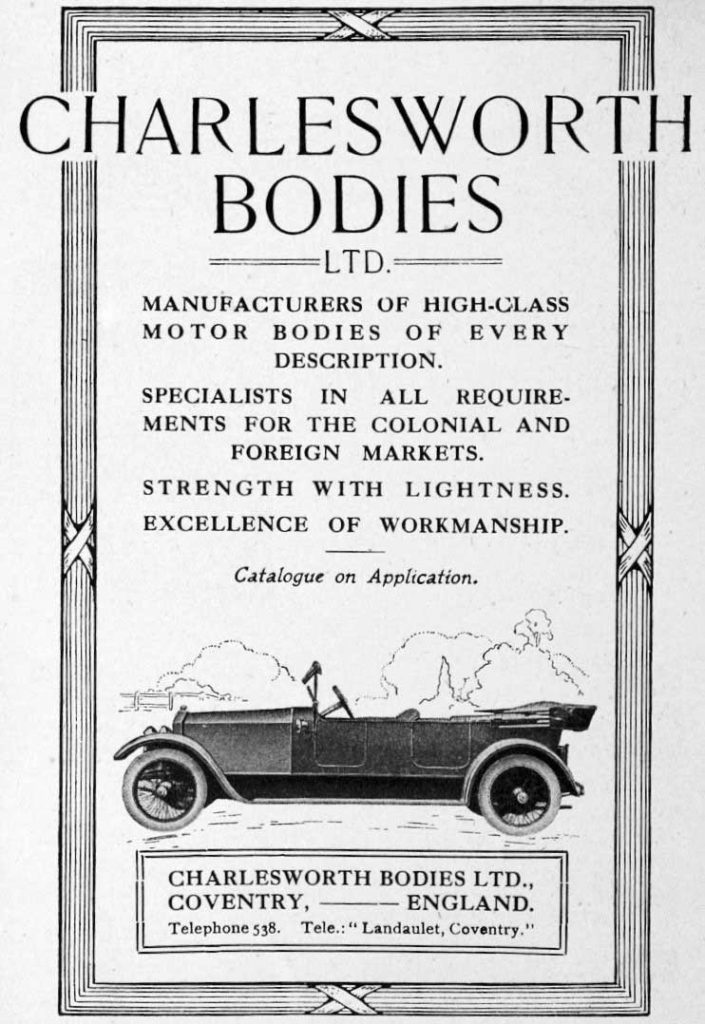

Clearly, Hill’s thoughts were turning elsewhere and the Singer connection was probably influential in the decision to join forces with Charles Steane to form Charlesworth Car bodies in 1907, in the Much Park Street premises.

Prior to that – and possibly more influential in the decision – was the fact that Hill had clearly run into financial difficulties. Perhaps he had stretched himself too far, for he had amassed considerable debts. The Birmingham Daily Mail reported, under the heading ‘COVENTRY CONTRACTOR’S AFFAIRS’ –

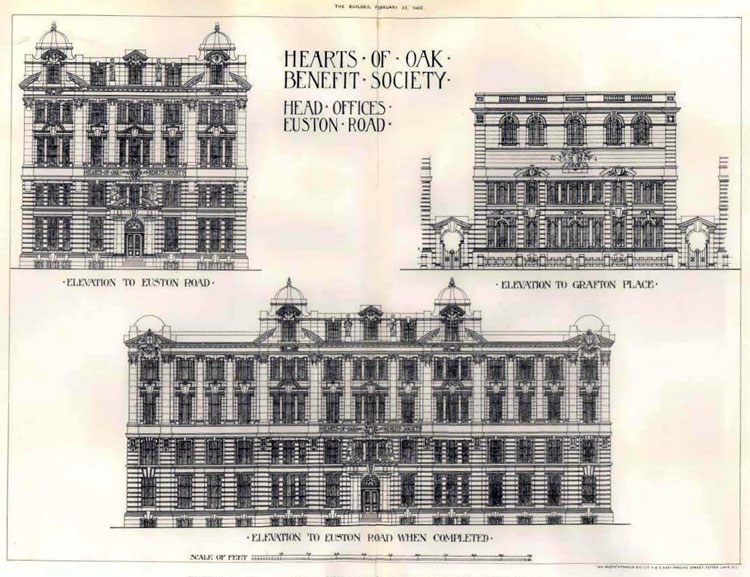

‘Under the failure of Charles Gray Hill, builder and contractor, of South Place, Finsbury, and Godiva Road, Coventry, which has been reported to the London Bankruptcy Court, the liabilities are estimated at about £40,000, and the assets are valued at sufficient to pay all debts in full. The debtor has carried out some important contracts in Warwickshire and London, among the number being the Hearts of Oak Buildings in the Euston Road, London, which was opened by the King early in the present year.’

The latter quoted building – the Hearts of Oak benefits Society – was a very large contract as indicated by these architectural drawings:

In February 1907, the Godiva Street stock and plant were up for sale, consequent upon ‘the failure of Mr. C. Gray Hill’. The size of the business is perhaps reflected in the Odell’s sales catalogue which ran to 58 pages with 1200 lots!

Charles Gray Hill also moved from Broadwater, for in the Coventry Herald of 12 April 1907, Charles B. Odell is advertising ‘the charmingly-situate modern residence late in the occupation of Charles Gray Hill Esq.’

George Singer died at Coundon Court in 1909, and the premises were soon put for sale. Included in the sales particulars is Coundon Court Lodge or Holly Lodge. This was itself of considerable size – 7 bedrooms, 3 sitting rooms, ample offices; stabling and garden; three cottages; fitted laundry; useful farmery. The details concluded with a simple description ‘Charming’.

Charles Gray Hill and his wife were beneficiaries of the Singer estate and the 1911 Census revealed that Charles Gray Hill now occupied Holly Lodge. He continued as managing director of Charlesworth until his retirement in 1928.

Rather than being explored here, the Charlesworth Bodies story merits inclusion in the motor industry section, but suffice it to say that it seems to reflect the entrepreneurial initiative and spirit of optimism typical of Coventry industry at the turn of the century.

It seems that Charles Gray Hill departed to Jamaica with his wife in 1933, only to return almost immediately. He died the following year at Abbey Spring, Beaulieu, Hampshire.

So the story of Charles Gray Hill contains much unanticipated material, revealing him as a significant builder in the city of Coventry (and beyond), with a sharp change of direction to the world of car-bodies early in the twentieth century. He certainly left his mark on the industrial history of Coventry.

Copyright © Martin Green 2020