Berkswell Windmill

Woman completes ultimate DIY renovation project

of one of Britain’s last fully working windmills

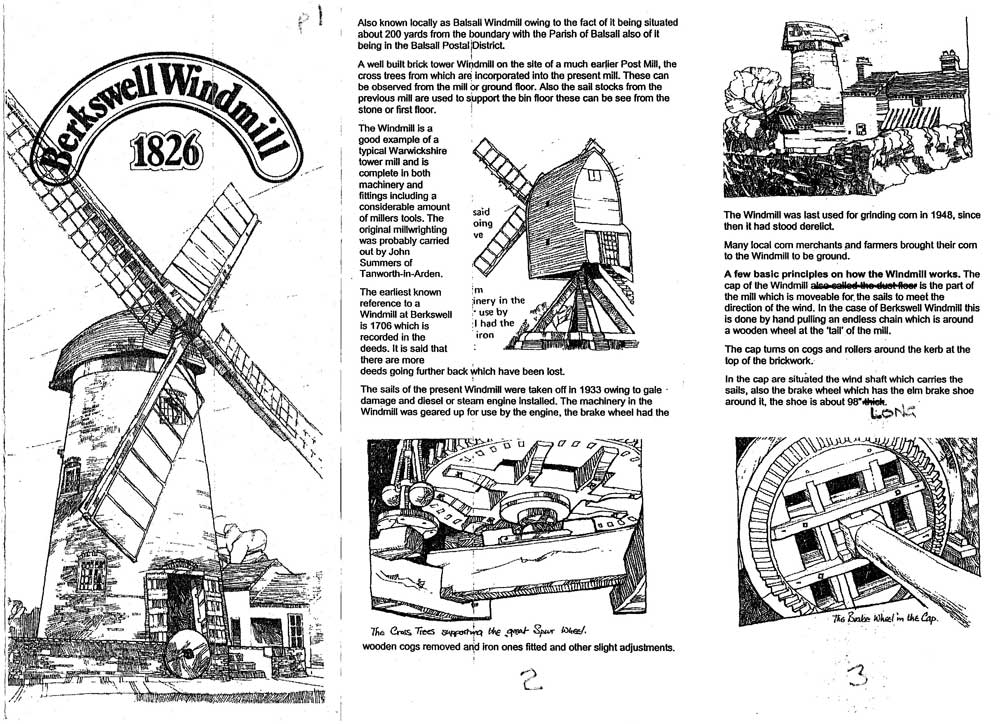

A homeowner has completed the ultimate lockdown DIY project of one of Britain’s last fully working windmills – after using a cherry picker to paint the sails by hand. Jeanette McGarry, 58, painstakingly spent three weeks hand- painting the gigantic five tonne sails as part of a refurbishment of historic Berkswell Windmill. The 70ft Grade II-listed building has been standing for nearly 200 years in the village of Balsall Common, West Mids., and was bought by Jeannette in 2005.

She then spent £200,000 restoring the 19th century four-bladed tower mill to its former glory with the help of English Heritage after it fell into a state of disrepair. It has been described as among the finest Georgian windmills in Britain and one of the most complete in the UK with all its original working parts and machinery. Jeanette has now taken the time during a local lockdown in her area to complete much-needed renovation work throughout September. The maintenance has involved continuous lime washing of the interior, dressing of mill stones and painting the huge sails with the help of a cherry picker to reach the top.

The mill is now fully operational and Jeanette hopes to welcome visitors back to the windmill once Covid-19 restrictions are eased. There has been one on the site as far back as the 10th century, built originally from wood and replaced with bricks in the Georgian period and the inside is a testament to the craft of milling. Mother-of-three Jeanette, who works in local government, said: I feel more like the guardian of the windmill rather than the owner of the windmill. I want to make sure that the windmill is preserved so it’s here for generations to come, along with the countryside around it. In terms of what’s it like living here, every morning when I wake up I feel blessed. I feel like the luckiest person on the planet really, because it’s just such a beautiful sight. If it is snowing, if it’s windy, if it’s sunny, the windmill never fails to bring a smile to my face. It’s absolutely beautiful. It’s all the history that goes with it.

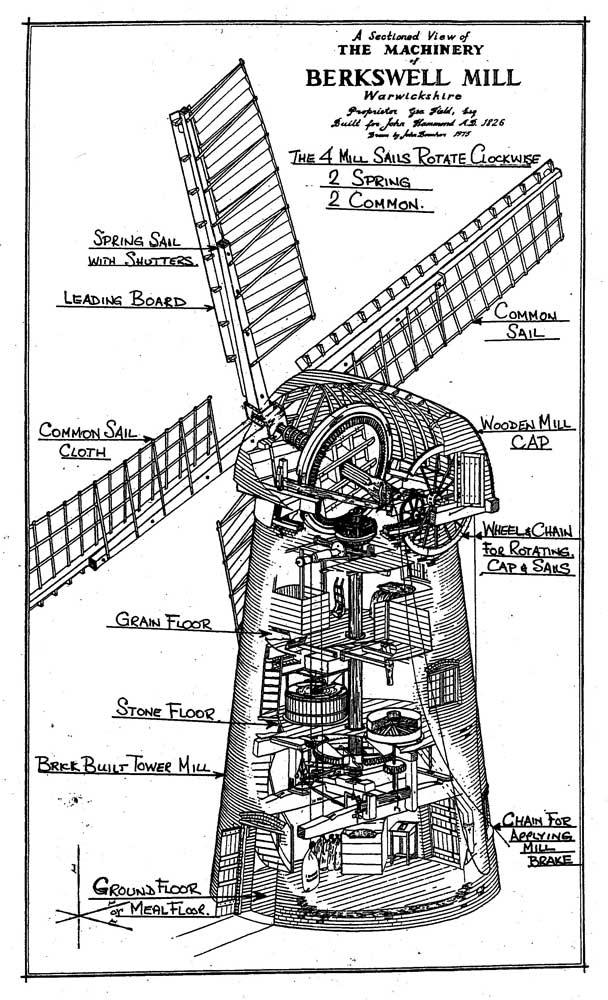

I really marvel at the windmill, in terms of how they were built. To me, it’s like the British equivalent of the Egyptian pyramids. They didn’t have cranes back in the day. They didn’t have precision instruments. They did a lot of things by sight. The bricks would have been made locally as well as all of the materials would have been gathered locally. The roof of the windmill is known as a Warwickshire Boat Cap, so each county has its own style of roof. It looks like an upside-down boat, like a rowing boat. The roof can be turned so it moves 360 degrees, all the way around. You pull a chain at the back and that means the sales can face the wind.

It was last used as a commercial mill in 1948 by John Hammond and after he died, it was bought by retired couple George and Betty Field in 1972 who carried out repairs. They then, unfortunately, passed suddenly and it was left derelict for a period until Jeanette moved in 15 years ago. She said: On the day that I moved in with my ex-husband, people were coming in through the gates asking to look at the mill.

There’s always a lot of interest in the mill. I contacted Historic England when I first moved in and they agreed to help me to restore the windmill. They funded 70% and I paid 30%. I had to contact the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which was originally set up by William Morris. They have a list of millwrights, the people that work on windmills and they are the expert builders if you like. There are only about 12 in the whole country.

We had it completely restored. We had the roof taken off, which is known as a cap, and repaired. We had some of the bricks replaced that had just completely blown off. We also had the whole mill re-pointed because it’s a brick-built tower and had all of the sales replaced. Together the four sales weigh five tonnes. Like any building, any wooden structure, you need to paint the sales regularly so we try to do it at least every three years. We have to buy specialist paint from Scandinavia. It was pretty tricky during lockdown because it’s been hard to get hold of materials.

One is called Johan and is originally from Holland. He knows everything there is to know about mills and helps with the painting. The other, John Beddington, used to run the Charlecote Watermill and helped with the painting too. He is almost 80 and he loves to climb up the sails. I hired a cherry picker so that it would be safer to do the painting. The pair were there for three weeks in September, working tirelessly from 7:30am to 6.00pm to carry out the restoration of the mill in anticipation of visitors possibly being able to return.

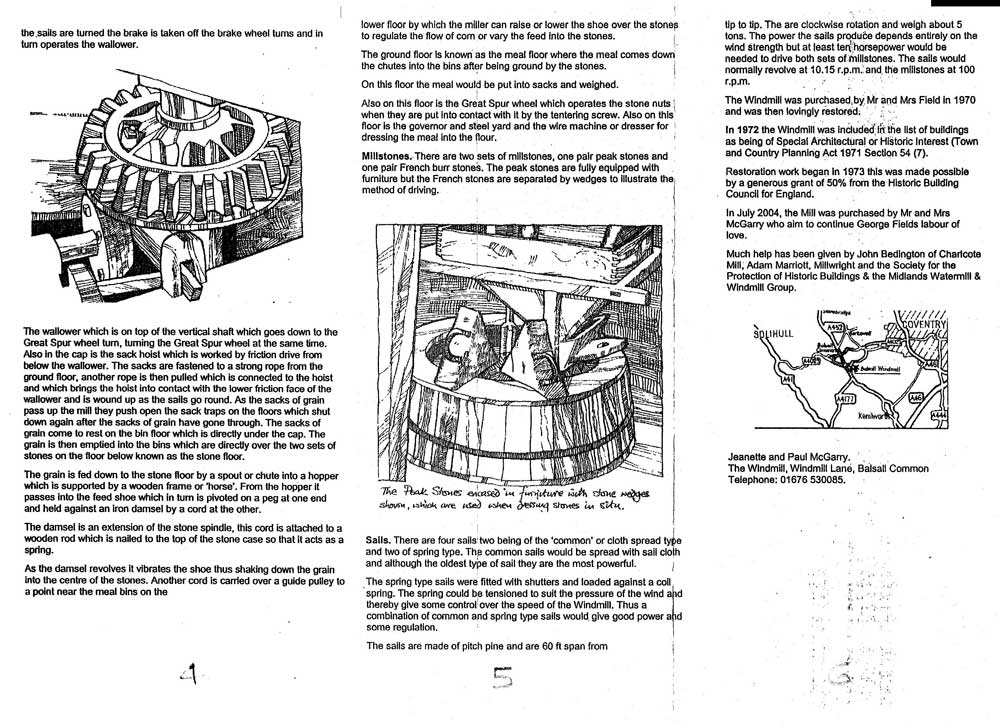

For the specialised Scandinavian paint, it costs £130 a tin and the hire of a cherry picker is £1000 a day. The interior is also given a coat of Lime wash, which is in keeping with the heritage of the mill as it predates paint itself. Jeannette said: It is completely operational. On the ground floor, you have the sacks where the flour comes out. The next floor up is the stone floor. There are two sets of massive stones, with four stones in total. Each stone takes at least five grown men to lift, they are really heavy. When you’re milling you have to lift the stones up partway through and chisel the pattern into the stone so that you’ve got some friction. It quickly gets clogged with flour so you have to lift those stones and re-chisel the pattern. The stones only come from two places in the whole world. The stones for fine flour come from France, the French Burr Stone. The stones for the coarse wholemeal flour come from Derbyshire, they are Peak District stones.

We really miss our visitors. Outside of COVID, we open once a month, with the help of volunteers, from Easter Monday through to October. We offer free guided tours and there’s cream teas as one of my neighbours bakes cakes. We have Morris Dancers and there’s always lots of audience participation. It is great fun to see the little children dancing. We also have the Coventry Spinners, Weavers and Dyers. They come along for every opening. There’s a real feel of history going on at the mill, living history. We also have a folk singer who drives all the way from the Cotswolds to be with us. So people are giving their time so freely, it’s incredible. One of the volunteers has a very large allotment and he often sells organic produce on the gate. We have somebody called Liam who runs the Young Millers Association and he’s got his own radio station. He broadcasts around the world from the windmill when we have our open days. The most interesting thing is you never quite know who’s going to step through the gates.

People say they remember coming here when they were children, just before or just after the Second World War. They came with their grandfathers or their parents to drop off some grain that the miller would be milling for them. We get people from all over the world coming. From America, Taiwan, Spain, all over the world. It’s a real joy, it’s really exciting and really interesting. I’ve actually got records from the 1700s of the miller here. It’s quite incredible when you go inside the mill, it’s just as it was when it was last used in 1948. It’s all the original machinery, all of the original cogs and wheels, which very few windmills have. It’s like a time capsule.

We’ve been talking to Solihull Council about the possibility of setting up an artist and business park in the area. There aren’t many trained people that can work on windmills in the UK, so we thought about a project where young apprentices could be trained by the older millers here. The skills could then be shared and continued. We could have artisan bakeries and supply the flour for them. It’d be a real positive to bring people through COVID and help him with economic regeneration.

I am doing some work with the University of Warwick at the moment. We are looking at the links between slavery and windmills. I have visited quite a few countries over the years, particularly in the Caribbean. There are windmills there used to make rum that are exactly the same as my windmill. The internal machinery came from Birmingham and the stones came from Derbyshire. They talk about Birmingham and the Black Country being the craftspeople of the world. It’s still alive and well in the Caribbean. It’s a real labour of love.

Stuart Robertson September 2020

Click here to see a short interview with the owner on ITV News

Martin Woolston also follows up Stuart Robertson’s piece on Berkswell Windmill with the attached drawings and text. Martin led a visit from his Greyfriars group to the windmill, and his usual inquisitive eye no doubt kept the guide on his toes!